Last August 22, 2024, as part of its 40th anniversary celebration, ICSI gathered more than 30 social development workers, mostly from its long-time partner NGOs, for a conversation on the state of civil society in the Philippines from the perspective of different generations.

The activity was designed to serve as a space for the participants to take a reflective look at the sector and its members. It adopted a method of “spiritual conversation”, designed to “strengthen the communion of hearts and minds, not to be confused with unanimity of opinion, so that the group may become a more discerning group.”[1] It had three rounds of group listening and sharing, followed by a plenary discussion.

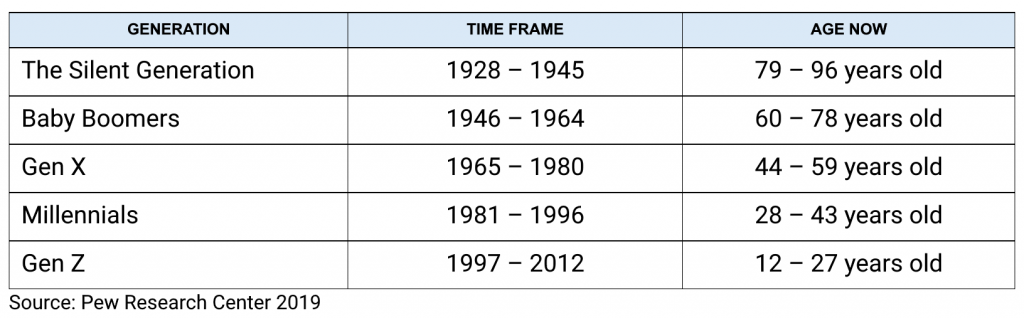

Grouped according to their “generation”, the participants answered the following questions in the First Round (also called “personal sharing”):

- What questions am I asking now about the state of the nation? (Anu-anong tanong ang tinatanong ko ngayon tungkol sa lagay ng bayan?)

- What questions am I asking about myself now that have to do with the nation? (Anu-anong tanong ang tinatanong ko tungkol sa sarili ko ngayon na may kinalaman sa bayan?)

- What am I doing now that has to do with the state of the nation? (Ano ang ginagawa ko ngayon na may kinalaman sa lagay ng bayan?)

- What do I want to do for the nation? (Ano ang gusto kong gawin na may kinalaman sa bayan?)

In the Second Round (called “reflective sharing”), participants shared what resonated with them from what they heard from others. In the Third Round, the group discussed the fruits of the session that they want to bring to the bigger group during the plenary session.

Below is a summary of the plenary session:

Finding hope and meaning. Hope for the country emerged as a common theme among the groups, especially the Gen Z and Millennials.

In their conversation, the Gen Zs pondered on the factors that led to the current situation where things seem dim and bleak, particularly for the sectors and communities that their respective organizations serve. They expressed commitment to the causes of democracy and social justice but admitted that they do deal with questions about alternative career paths. Moreover, the newcomers in the development work said that the prevailing sociopolitical and economic conditions pose challenges to finding “meaning” in their work.

One group of Millennials delved into the question: “Tama pa ba itong ginagawa natin? (Are we doing the right thing?)” Another group asked, “Are we doing enough?”, prompting the members to recognize a “crisis of imagination” among social development workers. Having worked in the social development sector longer than the youngest generation, the members of the group found themselves looking for concrete results and impact of their work. Doing so, one group explained, is a struggle because gains and wins are easily obscured by distressing social realities. Sustainability issues facing NGOs (i.e., decreasing funding and aging leadership) add to a sense of uncertainty among the millennial NGO workers.

Despite these, the Gen Zs still see themselves thriving in the development sector—as community organizers, researchers, and trainers—for they see their work as their service to the nation. There was also a yearning to learn more, especially from their interactions with people and communities. For some Millennials, their faith anchors them and gives them courage to carry on and remail hopeful. Many in their cohort are at a stage in their life where they juggle work, family, and personal concerns, but staying with their NGO to work for social good is starting to become a “calling.” Although there is hesitation in taking on leadership roles, the clamor for a more consultative work culture and for the involvement of younger employees in decision-making processes in some NGOs was brought up.

A sense of powerlessness. The “illiberal tendencies” of Filipinos, while acknowledged as part of social reality, bothered the Gen X social development workers. The group was troubled by how easily the members of organized communities acquiesced to politicians exhibiting values that contradict those espoused by the NGOs such as sanctity of life, human rights, and justice. For the group, the prevalence of vote-buying during elections and heavy dependence on politicians—all reflecting the lack of “sense of wrong” among citizens—indicates the powerlessness of people, especially the poor. This reality represents a colossal challenge for the already “thin” civil society in the Philippines, provoking the group to ask, “Hanggang saan pa ang kaya nating ibigay? (How much more can we give?)” Finding answers to this question, the group added, would not be easy as they, as individuals taking on executive positions, carry heavy responsibilities in their respective organizations. Nevertheless, the resilience of their organizations in the face of setbacks and challenges motivates them to continue contributing to nation-building.

The conversation among members of one group of Baby Boomers delved on the sociopolitical situation of the country, prodding them to ask: “May kinahinatnan ba ang ating pag-oorganisa? (Did our organizing of communities bear fruit?)” They admitted having been disappointed with the outcome of the 2022 national elections that brought back to power the Marcoses, the family of the late dictator against whom the veteran NGO workers and advocates fervently fought. They also wondered where CSOs had gone wrong—especially in forming or inculcating values—as millions still live in poverty and corruption in government remains unabated. Many NGOs—some in close collaboration with the Catholic church—have been organizing communities and sectoral groups but whether they have contributed to building the nation is a different question.

Building a movement. The Gen Zs and Millennials raised the idea of creating a movement in which civil society organizations overcome their differences and come together, especially on issues of governance. This is crucial, as pointed out by one group of Millennials, because NGOs and POs have become targets of “red-tagging” and protecting one another is important in keeping civil society’s work for democracy going. Such a movement can also be a platform for civil society to serve as a political force that can meaningfully challenge structures and systems. CSOs must not settle with token representation in decision-making and policy-making processes. As a movement, CSOs should also endeavor to increase their constituents’ civic and political engagement to gradually replace patronage politics and clientelism.

There have been efforts to build such a movement but as pointed out by one group, “tensions” between and among personalities, especially those belonging to the older generations of social development workers, come into play. Egos take over and collective actions lose momentum. Another obstacle to forging unity among CSOs is competition over resources for projects. Faced with financial constraints, NGOs tend to work on their own or with select groups only.

The Gen X saw more profound divisions within civil society. The 2016 elections brought to fore deep-seated differences among coalitions, networks, NGOs, and POs. The years that followed saw CSOs grappling with questions about their basis of unity and the values they thought they have been upholding. There were also realizations that NGOs have not been listening closely to people in the communities, therefore missing what really matters to them and how these influence their political choices. These will have implications for the “solidarity” that younger generations of social development workers said they wish to see.

For this movement to take off, one group of Baby Boomers said the reason for coming together—the “why”—must be clear.

Facing old and new challenges. Recognizing the efforts of the earlier generations of social development workers, one group asked, “Anong mga hindi nagawa noon na dapat ay gawin ngayon? (What was not done before that should be done now?)”

Another group of millennials pointed out the need to have “new frames of analysis” to understand pressing issues. Foremost of these issues is the emergence of artificial intelligence (AI), which has been used in a malicious manner to create disinformation and sow distrust and confusion. The popularity of social media, for the Gen X group, forces NGOs, especially those engaged in community organizing, to reimagine tried-and-tested strategies and tactics for mobilizing people around an issue. They must focus on engaging the youth as the next generation of voters and even leaders.

In terms of succession, the veterans in the social development work—those who have retired but could not leave their organizations as well as those who would retire in a few years’ time—are faced with the challenge of mentoring the younger generation of NGO workers. Given the present state of the nation and differences with the younger generations (e.g., in terms of worldviews, values, and work ethics), the work never seems to be finished for them. Building the resilience of the successor generation of NGO workers was a shared concern. The Gen X, in particular, said that they are aware of their responsibility to sustain their NGOs and “leave behind adequate human and financial resources.” The Baby Boomers expressed their struggle with understanding where the younger generations come from.

Celebrating our gains. One of the two groups representing the Baby Boomers underscored the need to remain hopeful. To do so, gains, no matter how small these may seem, must be celebrated, and losses, no matter how devastating, must be recognized. Trusting that a situation can change for the better, savoring the victories, and learning from failures will serve as motivations—for individuals, organizations, or movements—to respond to the challenges facing the nation. The group believed that now is the time for the younger generation to take over the social development sector and create its own narrative. (There was a suggestion, however, to also write about the narrative created by the previous generations vis-à-vis the nation’s history.) One member gave a timely reminder for the participants, especially the younger ones: “Ang layo ng ating malalakbay ay depende sa lalim ng ating patuloy na pagninilay. (The distance we can take depends on the depth of our continuous reflection.)”

The

intergenerational dialogue proved helpful in eliciting ideas and insights on

how the social development sector can and will navigate its future. The

conversation shall continue.■

[1] Sunny Jacob, SJ, “Spiritual Conversation and Communal Discernment”, November 17, 2021, https://www.educatemagis.org/global-stories/spiritual-conversation-and-communal-discernment/.