Homily

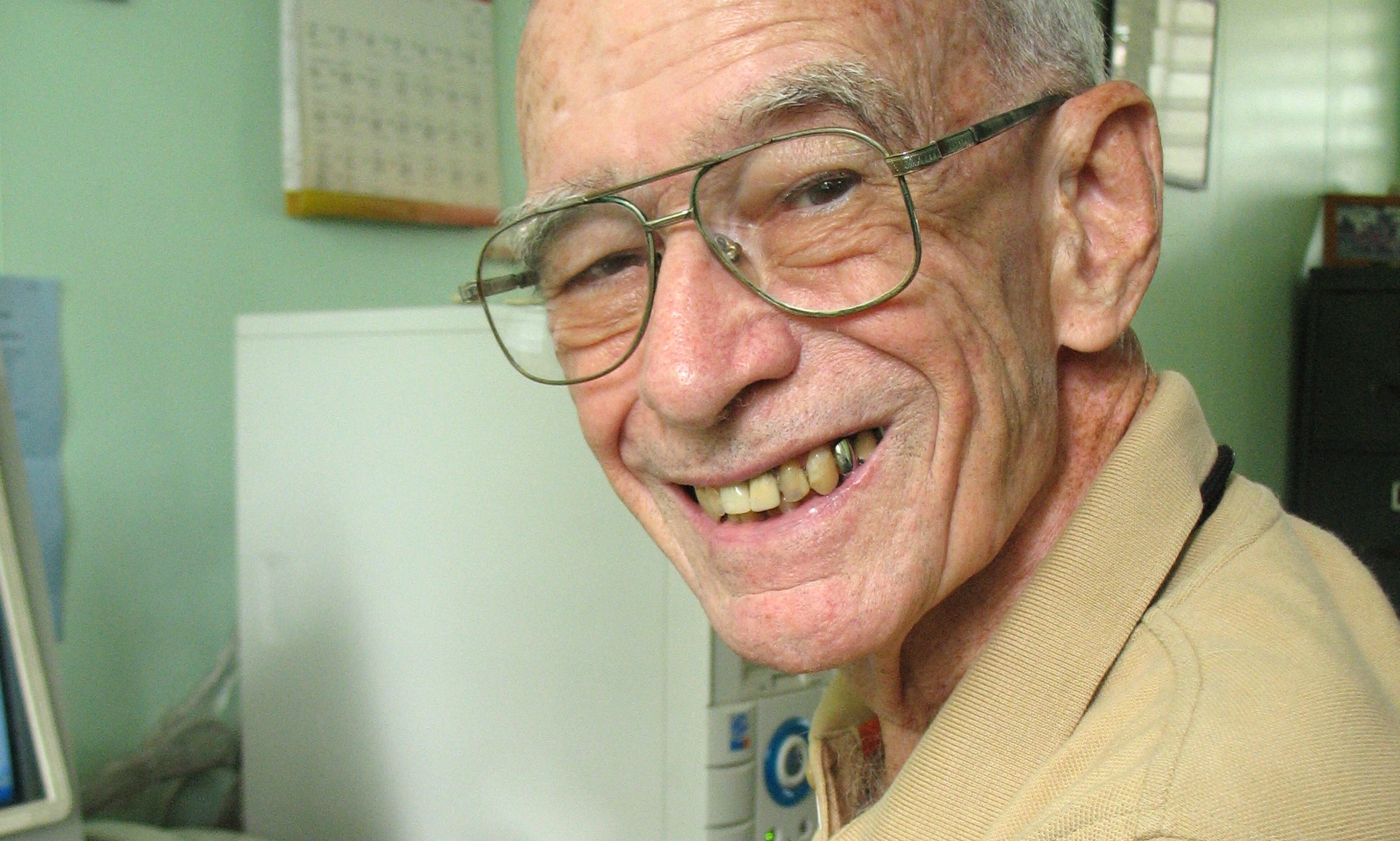

Wake Mass of Fr. John J. Carroll SJ

By Fr. Nono Alfonso SJ, 18 July 2014

“Namatay na ang tatay mo.” Your father has passed away. This was how a friend greeted me on learning about the death of Fr. John J. Carroll yesterday. It was a strange way of describing my relationship with Fr. Jack all these years. It felt odd because my own father died eight years ago. But at the same time, that description felt right, and true. In fact, Father Jack’s passing away feels like losing my father all over again. In a very real and profound sense, he was a father not only to me but to so many people (to many of you here, I am sure). In Father Jack, I now truly understand what the fatherhood of the priesthood means, how without a family of his own, the priest nonetheless becomes a father to God’s people.

I first met Fr. Jack when I became his student in an elective class at the Ateneo de Manila college. Little did I know then how that chance encounter would change my life forever. I saw myself then as a student activist and as an activist who rebelled against anything foreign. One time in class I got into an argument with him and said something like, “You wouldn’t understand because you are not Filipino!” To which he said, “Well, Nono, when were you born? I was already here after World War II!” Indeed, a native of New Jersey, Fr. Jack at 19 years of age entered the Society of Jesus in 1943, and in 1946 was sent to the Philippines as a Jesuit missionary. There was no turning back for this young idealistic Irish-American.

Except for some years of studies in the USA, and a stint as visiting professor here and there, including being Dean of the Sociology Department at the Gregorian University, Fr. Jack was stuck for ill or for good with the Philippines. It was as his favorite joke goes, his salt mines, the corner of God’s vineyard in which he happily toiled all his Jesuit life. He applied to become a Filipino citizen, but his social activism, during the Marcos years and beyond, he suspected, could have stalled his naturalization indefinitely. Even if, as I conceded in that college elective class, he was more Filipino than many of us in the love and service he has given to this country.

Despite our silly argument, Fr. Jack, at the end of that year, invited me to join the Institute on Church and Social Issues (ICSI), the think-tank group, the research and advocacy NGO which he founded with Fr. Ben Nebres and Bishop Francisco Claver at the twilight of the Marcos years. It was here that Fr. Jack would become my mentor. (Or tormentor, he would joke at times). A father mentors his children, gives them direction, and empowers them to face the world’s challenges and undertake their mission and calling in life. That was how Father Jack was to many of us at ICSI. He mentored Jesuit scholastics, many of whom have been ordained as priests, and have gone on to be leaders of other Jesuit institutions. we have Fr. Jojo Magadia, who became Provincial Superior, Fr. Jun Viray and Fr. Bobby Yap, Ateneo presidents, Fr. Robert Rivera, Social Apostolate Director of the Province, and Fr. Pedro Walpole, environmentalist. Fr. Jack set them off to their missions. There were many lay people as well who worked with Fr. Jack at ICSI, graduates from the Ateneo de Manila and other prestigious universities, letting go of fat salaries in the corporate world to work for the poor and the marginalized whom ICSI served.

There were many others who orbited around ICSI and Fr. Jack. Like his colleagues in the academic community, or the many bishops who would ask for wisdom and advice on certain social problems. And of course, there were the anawim, God’s poor. Although Fr. Jack became popular with his columns in the Inquirer, he was no armchair revolutionary. For thirty years, he presided at Sunday masses in Payatas, raised funds for a feeding program and for the scholarship of many promising children there. These are the people whose lives were touched by Fr. Jack and who now grieve because they have lost a mentor, a father.

The passion for the social mission of the Church, for social justice was something that he was able to pass on to many of us. But equally important is the rigor for the quality of our work. This was one thing I learned from Fr. Jack. There was no room for mediocrity at ICSI. Indeed, as many of my co-workers in ICSI would tell you, Fr. Jack was a slave driver. He was very passionate about his work and expected the same from all of us. In just a few days at ICSI you would be able to memorize Fr. Jack’s motto. “Change takes time, and therefore there is no time to lose,” he would tell us repeatedly, and then add, “So, back to the salt mines!” Deadlines were very sacred to him. One time, we were planning for an issue of our newsletter. He asked me when I expected the issue to come out. I replied by saying, “God-willing….” but he cut me right away and said, “Please, leave God out of this!” Oh, ok, Father. At another time, I made a minor mistake, he asked to see me in his office. I was trembling with fear, expecting to be fired. After hearing my story, he simply said, while grinding his teeth, “Well, Nono, to err is human, BUT to commit the same mistake, that would really, really be stupid!” I did not commit the same mistake. I made other mistakes.

Fr. Jack was passionately serious with his work, with his mission. Because the stakes are high, he would always remind us. The children scavengers of Payatas, the millions of farmers deprived of land to call their own, the millions more of the urban poor living in inhumane, squalor conditions — all these are waiting for salvation, for a precious chance or opportunity for new life — what if you could lift a finger to help them, would you not do that, for them?

In a sense, Fr. Jack was strict. But never cruel. And he had a gentle side. I remember some serious conversations at ICSI and then many more after I joined the Society of Jesus. In these long personal conversations, I would share about family problems, personal struggles, and at the end of our talks, I would always hear him say, “Courage, Nono. Courage!” And that was enough. It said a lot. You can do it. I believe in you. I trust in your strength. Every time he felt he has offended someone, he would right away try to clear the air, and apologize. Like that “leave God out of this incident.” He went to me later and said sorry if he were harsh.

Fr. Jack knew that he could sometimes be very determined, especially at work, and in the process hurt people’s feelings. He was humble enough to say sorry every time this happened. A friend of mine described him best when she said, Fr. Jack was also a work in progress, he mellowed down through the years, the mentor, the teacher learning from his students. And perhaps it was this humility that made him a friend to many as well. Not just a mentor or teacher, but a friend. A friend who was accessible, a friend who would teach you to swim — yes, he offered swimming lessons every afternoon at the Cervini pool – or simply eat burgers with you, burgers being his favorite.

In the past six or eight years, Fr. Jack’s health condition became difficult. He had many surgeries and operations. He was in and out of the hospital. I would visit him every now and then. In the hospital after an operation, or in his room here at LHS. It was difficult to see him, this great Jesuit who accomplished great things in his life, reduced to this small crumpled sick man. He would struggle, like many of us. He still wanted to be of service to the Society and the Church and the poor he loved so much. He told me one time how he felt lonely and powerless in his small room at the infirmary. I brought him books to read, even bought him audiobooks, CDs and DVDs. He was still writing for the Inquirer at this time. His last article would you believe was last March 1. Wow. He wrote a piece on the passing away of a friend, Fr. Montecastro. And I am sure, he was writing about himself as well. He wrote:

“But then came a stroke, an operation on his throat, and some 10 years of speechlessness, confinement to bed, years of being much of the time alone with his God. I am sure that they were years of purification, the setting aside of earthly plans and desires and putting himself in the hands of the Lord—something which was evident in the peaceful smile with which he greeted visitors even when he could not speak. And so on that evening as the sun went down and the bell tolled, Monte could say with St. Paul: “I have fought the good fight to the end. I have run the race to the finish. I have kept the faith; all that is to come now is the crown of righteousness reserved for me.”

I am sure, Fr. Jack spent his last years learning more and more to surrender to the will of God. Two years ago, as he celebrated his 70th year in the society, he said, “It’s been a great, if sometimes bumpy ride. As I look back on 70 years in the Society, on three continents, and recall the thousands of students, co-workers, and urban poor whom I have been privileged to know and serve and call my friends, I am amazed at the Lord’s generosity.”

This is the last lesson I hope I have learned from Fr. Jack, my father, mentor and friend. To be able to say yes to the great beyond when my turn comes. To say with Christ, into thy hands I commit my spirit. Fr. Jack, thanks for being my spiritual father. Thanks for mentoring us. Vaya Con Dios. “Courage, Jack, Courage!”

Originally posted on phjesuits.org.